Wearing Your Heart on Your Shoes

A Profile on Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçons

1942 – Rei Kawakubo was born in Japan to an educated family. Her mother and father got divorced during her childhood over her mother’s desire to pursue a career, leaving Kawakubo to carry the weight of feeling like an outcast amongst her peers. Kawakubo accepted this outcast mentality and used her clothes and aesthetic to define herself on her own terms.

While being one of the most well-known and venerated fashion designers ever, she never attained any formal training in fashion.

According to the youtube account Threaducation (who sit at 175 thousand subscribers), their biography on Kawakubo, she used her degree in fine arts to get a job as an advertiser for a textile company in Harajuku, Japan’s most fashionable district. Designing clothing to highlight her employer’s textiles, she began to make a name for herself in the fashion space. Eventually, she became disappointed with the state of Japanese fashion at the time, struggling to find clothing she was moved by on the shelves of the Harajuku stores.

So, in 1969 at the age of 27, she launched the brand Comme des Garçons.

The name “Comme des Garçons” is of French origin, meaning “like the boys”. It comes from a song by Francoise Hardy titled “tous les garçons et les filles”. The song speaks to being a social outcast unable to find love.

Living in the world of the color black, she dared her clients to venture into her psyche. By 1981, her avant-garde and striking black designs propelled her work to Parisian runways, where all the eyes of the fashion media were planted. Befuddled by her work, the fashion landscape was polarized but simply could not get enough, and her commercial success skyrocketed.

The mainstream media was never too keen on accepting her work, as they couldn’t place it in a box. Tattered or disorienting luxury garments in striking black indirectly spoke against the prevailing moods of fashion at the time. As they say, sex sells. Unless it doesn’t…

The fashion media put her into the category of other like-minded designers of the time, such as Yoji Yamamoto, and her western contemporary, Martin Margiela, calling their work “anti-fashion”. But this term is reductive to every one of the designers mentioned above. Kawakubo’s work was uncategorical, untouchable, and never before seen. These “anti-fashion” designers had more differences in their work than similarities. The inability of her work to be unilaterally categorized for the western media to anoint or dispose, speaks to the power of her clothing. People around the world found themselves entranced by her work and no amount of media belittling could take that away.

While designers and trends fade in and out constantly, sustaining a high level of notoriety and commercial success can prove to be the most difficult ordeal for fashion labels. The commercialization of fashion in the turn of the 21st century was led by many mainstay fashion houses launching diffusion lines with a heavy emphasis on products that mass consumers could purchase. The Comme Des Garçons identity did not fit well into this business model. Kawakubo took this opportunity to create the mass-market consumer line Comme des Garçons Play.

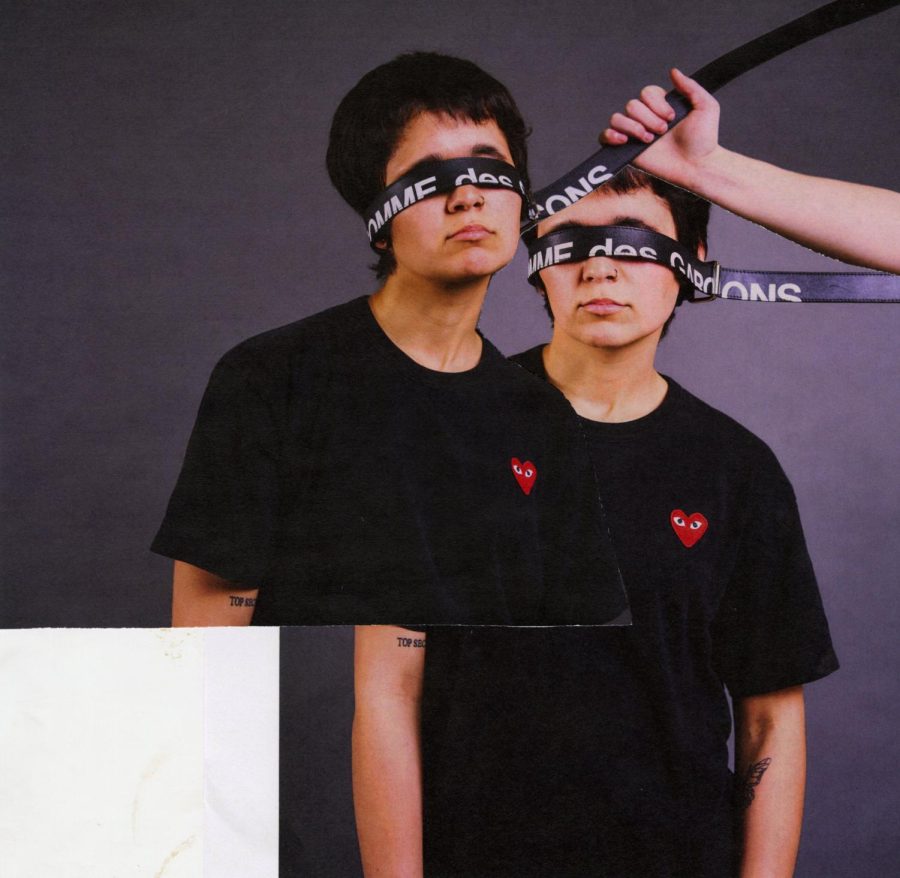

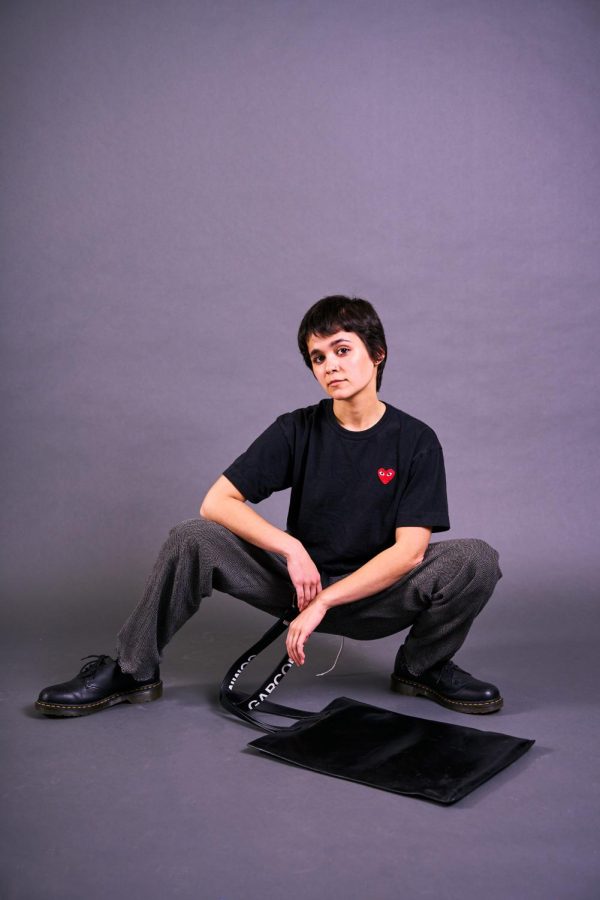

As opposed to the black monotone pieces that had defined her career up to that point, CDG Play was meant to be fun and not too serious and is well known for the heart logo, which is featured on countless pieces today, most notably, in the collaboration with Converse.

The logo was designed by Filip Pagowski in the 1990s and was given to Kawakubo. Funnily enough, Kawakubo initially had no clue what to do with his design, as her work rarely featured graphics or anything of that nature. CDG Play launched in 2002 and the pieces with their infamous heart logo applique quickly flew off the shelves. The brand was an instant success, transcending the fashion industry becoming familiar in the wardrobes and minds of contemporary culture today.

The immense success of CDG Play not only cemented Kawakubo as one of the most influential designers and business women of her generation, it also relieved the stress of her mainline design’s needing to be commercially successful. While CDG Play racks in millions of dollars and exposes new people to her work, her mainline creations can continue to push the boundaries of art and fashion.

To Kawakubo, the runway show is the most vital aspect to the entire creative ordeal. As her clothing walks down the runway you see the way every ruffle, every pleat, every gather moves and sounds in accordance to her creative vision. The unique spectacle of her shows is why so many people love her brand. Brands show collections at the myriad of fashion weeks throughout the calendar year. Whether it be in Milan, London, New York, Paris, Beijing, or Japan these fashion exhibitions are exhaustively expensive especially for less commercially viable designers. Brands have to spend between one hundred thousand to three hundred thousand dollars to be able to put on a fashion show any given season. Some of the largest brands will spend upwards of one million dollars, using their power and influence to put on spectacles of imagination and human creation for their clientele and influential guests. These expenses added up quickly and the positive impact on return on investment is minimal at best.

For this reason, the brand showed their Spring 2021 collection in October of 2020 to a live audience despite the incredibly dire state of COVID-19 globally.

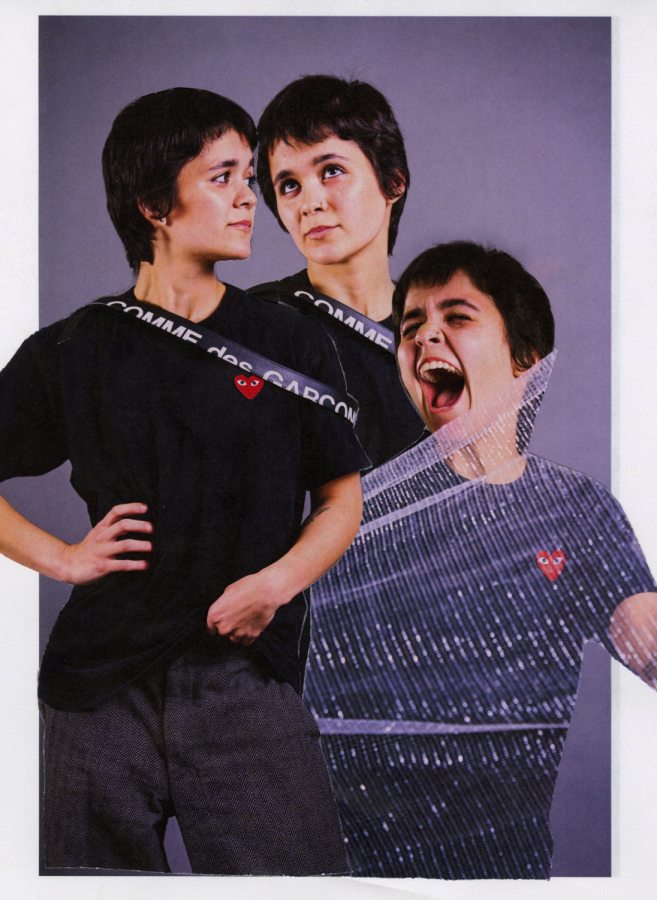

In a room of 16 people, the live audience covered in both masks and plastic face shields witnessed the powerful collection that encapsulated the anger and confusion that people felt at the time. Red light flooded the concrete space as models entered the small capsule dressed in voluminous clothing in red, white and black. Stiff and structured pieces with crinoline frames provided its wearers with a protective bubble from the dangerous and outraged world. All those who attended wore both face masks and clear plastic facial shields to remain protected. This was mirrored in the runway show as almost all the pieces that went down the runway were covered in a heavy clear plastic film. Through the translucent barrier, the world was kept at bay.

An enraging red Yutaka style dress contained by white edge finishes with powerfully feminine puff sleeves gives way at the sternum to a gaudy overlaid Minnie Mouse print that descends to the bottom hem of the dress until the abrasive graphic is interrupted by illegible black and white graffiti. Pleating gives the dress volume, structure, and drape that is all the more emphasized by thick translucent film that mirrors the dress as it hangs on the body. Does the translucent film protect the traditionally comforting ideas of Japanese culture and nostalgia filled motifs from an outside world rash with disease and disorder despite the apparent vandalism that has already taken place? Or does the film provide a safe window as we the viewer voyeuristically watch a world of order and status quo descend into anarchy as the result of being sold a false promise of carefree happiness that we all feel we righteously deserve?

Kawakubo’s work is so enigmatic when it is first shown because they are so of the moment, attempting to understand them from a referential or more literal perspective falls flat and is more or less impossible. Kawakubo’s work is like looking at art through a microscope or a telescope; “true” context and societal understanding isn’t what Kawakubo is communicating. Rather her work speaks to her personal emotions at the time of designing her collections. Rarely speaking to the media, Kawakubo prefers her work to do all of the talking, allowing for her supporters and critics to derive their own meaning from her work. Shouldn’t that be the point of fashion anyway? Fashion should not be about social status or persona and body image, it’s not sustainable. Not sustainable for the environment that we exhaust to buy clothing so our peers will think we fit in, not sustainable for the bodies of the countless people who develop disordered eating as a result of trying to maintain an image of health and wellness, and not sustainable for our minds as we attempt to create a likable character in the way we dress.

When someone challenges a piece of clothing as unwearable, it speaks more to the identity of that individual. As Kawakubo said for Vogue Magazine in 2020:

“The human brain is always looking for harmony and logic. When logic is denied, where there is no logic, when there is dissonance… A powerful moment is created which leads you to feel an inner turmoil and a tension that can lead to finding positive change and progress”.

There are no reference points, this isn’t meant to be worn like a graphic t-shirt. It’s supposed to make you uncomfortable. The only tangible reference is to the emotion the pieces evoke within you. The pieces are for you to sit with, to question, to grieve, and eventually take lessons from. Her mission is to experience something totally unseen before. A child feeling insecure for the first time, the mental and physical isolation of the pandemic, or when nervousness turns to excitement as you jump off a high boulder into the water below.

As 2023 is now upon us, Kawakubo is nearing the end of her life. On October 11th of this year she will turn 81-years-old. It is mind bogglingly impressive that anyone of that age could muster up the energy, passion and inspiration to design the soul evoking pieces that she has been known for over the last 50 years. Oh, and not to mention, she still is in charge of a total of 29 other brands under the Comme de Garcon umbrella, all retailed at the 8 Dover Street Market locations worldwide. Dover Street Market itself was another fashion retail innovation opened by Kawakubo and her business partnered in 2004 to sell her work and the work of other avant-garde designers in a retail space that contributed to the unique artistic vision of the various designers featured in the space giving voice to younger generations and protecting the sanctity of avant-garde art for her posterity.

Kawakubo’s body of work speaks for itself, and she will likely continue to create until the day that she dies. Where other designers struggle to rehash popular ideas attached to trend cycles to maintain financial success and notoriety, Kawakubo speaks her mind into existence.

There will never be another Kawakubo and so there will never be another Comme des Garçons. I encourage you to explore her work further testing yourself and your assumptions about what clothing means to you and your environment.

Archive*:

Spring 1997 Dress Meets Body, Body Meets Dress (aka lumps and bumps)

Spring 2021

CDG Shirt FW 2020 Menswear

Dover Street Market.com

Fashion is a conversation that is ongoing, please feel free to reach out to @nate_olsen12 on Instagram to share your insights and opinions. Stay happy, stay healthy!